Articles

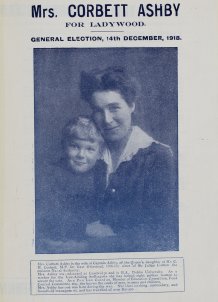

Margery Corbett Ashby, who stood as a Liberal candidate for Ladywood, Birmingham, used a picture of her with her son on the front of her election address.

First women parliamentary candidates utilised their gender to win votes, records show

Britain’s first female parliamentary candidates utilised their gender as a campaigning tool to win votes and championed new policies such as equal citizenship, analysis of records show.

On 21 November 1918, the Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act was passed which enabled women over the age of twenty-one to become MPs. As the general election was set for 14 December, this gave women very little time to organise themselves.

The pioneering women who stood in the 1918 General Election a century ago emphasised to the electorate they had the unique skills and experiences which would benefit Parliament during Britain’s reconstruction after the First World War.

Historian Lisa Berry-Waite, from the University of Exeter, has uncovered the election literature for all of the 17 women who stood in the historic 1918 election, in which women over the age of thirty who met the property qualifications could vote for the first time. Her work focuses on the election addresses of women candidates between 1918 and 1931 and is part of the wider Age of Promises project, funded by the Leverhulme Trust.

The election addresses haven’t been examined in great detail before and many of the first women candidates have been forgotten in history. Women aimed to capture the votes of newly enfranchised women, campaigning on issues such as equal voting rights and better housing. However, they were cautious not to alienate male voters, and praised the bravery of the soldiers and sailors who fought in the war.

Lisa Berry-Waite said: “In the celebration of partial female suffrage this year, it is sometimes forgotten women still had to argue for their place in Parliament. The first women candidates utilised their gender, arguing that the ‘woman’s point of view’ was needed in Parliament to represent the needs of women and children.”

“From reading their election addresses, you get a real sense of who these women were, what they were passionate about, and how they refused to apologise for their gender. The 1918 General Election saw a significant focus on ‘women’s issues’ for the first time.”

The research is the first detailed analysis of women candidate’s election addresses in the interwar period. The 1918 election addresses were discovered in numerous archives around the country, from the University of Bristol’s Special Collections, to the Imperial War Museum.

Most of the women had been involved in the suffrage movement previously. None were selected to stand in safe seats, given the novelty of a woman candidate. Only one woman was successful in 1918, the Sinn Fein candidate Constance Markievicz, but she refused to take her seat over Irish independence. The first woman MP to take her seat in the House of Commons was Nancy Astor, who won in a Plymouth by-election in 1919.

Mary Macarthur, a Labour candidate in Stourbridge in 1918, promised to voice the “aspirations” of women workers, saying: “I DO NOT APOLOGISE FOR MY SEX. It takes a man and a women to make the IDEAL HOME and I believe neither can build the IDEAL WORLD without the help of the other. In the new Parliament, where laws affecting every household in the land will be framed, the point of view of the MOTHER AS WELL AS THE FATHER, should find expression.”

Macarthur, who said her campaign was financed by the “pennies” of female workers across the country, said if elected she wanted to “speak for the women whose work never ends – the women in the home who faces and solves a multitude of problems every day – the woman who too often has been forgotten by politicians, the mother of the children upon who the FUTURE PRIDE AND STRENGTH OF THE NATION DEPENDS.” Macarthur’s background was in the trade union movement, in 1903 she became honorary secretary of Women’s Trade Union League and in 1906 she founded the National Federation of Women Workers.

Eunice Murray, who stood as an Independent candidate in 1918 for Bridgeton, Glasgow, said: “I am standing for Parliament because I want to assert to the fullest extent the right of every citizen, regardless of sex, to fill positions of trust and to share in the work and the government of the country; and because I am convinced that the country will benefit unestimably by the representation of the women’s point of view in parliament.” Murray was a suffragist and a member of the Women’s Freedom League. She wrote numerous suffrage pamphlets and letters which were published in the press.

Murray promised to secure “rescue and reparation” for women victims of the war, and said she would “demand the setting up of courts to search for the women who are missing and to punish all officers and men guilty of deporting, selling, and allowing outrage and brutality and sanctioning the deporting and forced labour of women”.

Former President of the National Federation of Women Teachers Emily Frost Phipps, who stood as an Independent for Chelsea, told voters it was “desirable” to have women to help settle affairs of the nation. She asked people to follow example of Canadian soldiers who had elected a woman. Phipps was a headteacher and also a prominent figure in the Women’s Freedom League. She boycotted the census in 1911 by sleeping in a cave with friends in the Gower Peninsula.

Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, who stood in Rusholme for the Labour party asked in what she described as a “special letter to women voters”, for people to “let the world see what women can do now, when they have the chance”. She went on to state that she had “given many years of hard work in helping to get votes for women”. Pethick-Lawrence and her husband were prominent members of the WSPU, she was imprisoned numerous times for her militant activities and was force fed in Holloway goal. Nonetheless, the Pethick-Lawrences were ousted from the WSPU in 1912 and between 1915 and 1922, she became treasurer of the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom.

Violet Markham, a Liberal candidate in Mansfield, stood in the seat previously held by her brother, who had died in the war. She told voters her brother’s friends had persuaded her to campaign, and that if elected she would give up her seat in a year so returning soldiers who were not yet home from war could have the right to vote. Interestingly, Markham had been a leading anti-suffragist before she changed her views on suffrage during the war.

The one Conservative candidate, Alice Lucas, stood in place of her husband in Kennington, London, who died three days before the election. She only had time to release a brief statement to the press.

Margery Corbett Ashby, who stood as a Liberal candidate for Ladywood, Birmingham, used a picture of her with her son on the front of her election address. She made sure to tell voters she was the wife of a soldier still in Belgium – including a picture of him in military uniform with the slogan ‘A Soldier’s Wife for Ladywood’. She was an active suffragist and became secretary of the NUWSS in 1907. She noted in her address “As a worker for the Law-Abiding Suffragists she has helped eight million women to secure the vote.”

During this election, “coupon” candidates were endorsed by the coalition government – Lloyd George Liberals and the Conservatives. Christabel Pankhurst, who stood for the Women’s Party in Smethwick, was the only woman to receive a coupon from the government. As Pankhurst was a former leader of the WSPU, her election campaign was watched with great anticipation. Nonetheless, she lost by just 775 votes. In her election address, she emphasised that she supported a “Victorious Peace and National and Imperial prosperity”. She utilised her gender, noting “As a Woman Member of Parliament, I shall, if elected, give special attention to the Housing Question, because, as every woman knows, a good home is the foundation of all well being.”

In total, five women stood as Independents, claiming to be above party politics. This is not surprising given many women had become alienated by party politics during the fight for the vote. Four women stood for Labour, four stood for the Liberals, and only Lucas stood for the Conservatives. Pankhurst was the only Women’s Party candidate, and two women stood for Sinn Fein, Constance Markievicz and Winifred Carney.

In this centenary year, it’s important to celebrate these pioneering women for their bravery and commitment to equality and justice. Whilst only Markievicz succeeded, these women paved the way for future generations and proved women were capable of standing in parliamentary elections.

Date: 13 December 2018